1) Tell us about when you first became interested in poetry. Who were your first poetic influences? When did you begin writing poetry? What do you think poetry does or can do for us today and does this differ from your earliest conceptions of what poetry is/does? etc.

It doesn’t make for a good story but I first started writing poems when I was in 9th grade. I had to write a paper on Sylvia Plath for English class.

As an undergraduate I was influenced by Russell Edson, Plath, Frank O’Hara, James Schuyler, Ezra Pound, Joseph Ceravolo, Michael Palmer, Robert Creeley, Frank Stanford, Jack Spicer, Mina Loy, Bernadette Mayer, Ted Berrigan, Keith Waldrop, and the Fluxus and Abstract Expressionist movements in art.

Later I became interested in Louis Zukofsky, Lorine Niedecker, James Tate, Nicanor Parra, Pablo Neruda, and the fiction writers Lydia Davis and David Markson.

Most recently I’ve been influenced by Edwardian fiction, Shelley, Emily Dickinson, and some younger writers, many of whom I know personally to some degree. I think a feeling of connection with a writer is necessary for influence, which is why many writers are influenced and inspired by their contemporaries: Thoreau by Emerson, Fitzgerald by Hemingway, Shelley by Keats, and vice-versa. But it’s possible to feel similarly connected to a poet who has been dead for 200 years just by reading his poems.

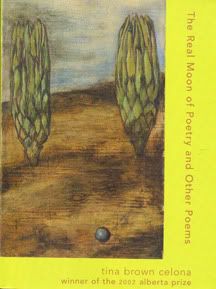

2) Give us some background on the creation, development, and gestation of The Real Moon of Poetry and Other Poems. How does this collection differ from your previous collections or current projects? etc.

About 80% of The Real Moon of Poetry was written while I was working on my MFA. I had published a couple of the poems in Epoch, a literary magazine based at Cornell, and a classmate had done a chapbook for me that included what was kind of a breakthrough poem for me, but which I didn’t include in TRMOP. It was called “Not Modern But The Modern World” and it was a breathless and slightly hysterical expression of angst.

My second collection, Snip Snip!, wasn’t as successful as TRMOP because I wrote the poems over a shorter period of time, and with on the one hand a kind of overblown confidence in myself, and on the other bleak depression and insecurity. It was a very egotistical book.

Since completing the coursework for a Ph.D. I feel like I have a more solid understanding of what poetry is, and how it has changed over time. Reading Aristotle and Horace on poetry, and then Alexander Pope and Shelley and Emily Dickinson, gave me a different and fuller understanding of poets and readers of poetry, what people come to poetry for. The relationship of poetry to emotion and imagination, for instance, is something that I think I understand better now than I used to.

3) What is your favorite or most memorable poem from the collection we're reading? What about the poem, its process, or its inspiration makes it particularly remarkable for you?

A poem that stands out for me (and other people, from what they tell me) is “A Poem Without A Camel.” That was designed to be a very accessible poem that worked on the principle of metonymy and metaphor. The camel can be anything you want it to be, but for me it was something pretty specific and also general: any prohibition applied to poetry. So the person writing the poem without a camel was doing what everyone said you couldn’t do, finding out that it wasn’t impossible after all. People have told me the poem is sad. It is both exhilarating to write without a camel, and sad when one wants the camel again and can’t have it. “The Velveteen Rabbit,” a children’s story by Margery Williams about a toy bunny whose boy grows up and forgets him, probably had an influence on this poem.

4) What was the most difficult poem for you to write? Why? How did you overcome or think through these challenges?

For me the difficulty lies not so much in writing poems as in publishing them. So, the poem that was most difficult for me to see in print was probably “Farm” or “Fantastic Heart” or “Poet Sex” or “On Saturday” because they were so deliberately ugly and self-punishing.

To me a poem is either a success or a failure. Poems that are easy to write tend to be successes. Some poems require more preparation and study than others. Fiddling with a poem rarely makes it better. Lopping off lines, stanzas, paragraphs, sentences, and phrases often makes it worse. If you are trying too hard to write a poem, you are probably either tired or uninspired. In that case you should stop writing and do something else until you find something that inspires you, and get some rest. But don’t expect inspiration to fall into your lap. While you are waiting for it you should be filling your head with words, ideas, images, and reacting emotionally to life, and simulacra such as books and movies. Think of this as preparing the ground for a poem, so that when the seed of inspiration falls into the furrow it has an excellent chance of growing into a beautiful flower or majestic tree.

5) What, to your mind, is the overriding concern of The Real Moon of Poetry? How do specific craft or poetic elements contribute to, intensify, or complicate to this concern?

The Real Moon of Poetry is about loving poetry while simultaneously being tormented by one’s desire and need for it. Ugliness and beauty, love and longing, fear and contempt. The white moon of poetry and the black crow that pecks at your entrails. Even more than “what is poetry?” the poems ask “is this poetry?”

I think that the poems are pretty forthright in the way they address these polarities, and metaphysical or existential problems are solved by application to real or imaginary-world situations. Feelings are invested in things and the things (or, more precisely, the words for them) in turn produce feelings. Images or symbols you might call them instead of things, but to me it makes more sense to think of words as objects in the poem’s field. The imagination is affected by things, or images of things, abstractions don’t awaken it. Poetry is different from other types of human inquiry because its form is self-evidently necessary, so that it can never be superseded or transcended by content (its body can never be left behind or forgotten).

No comments:

Post a Comment