1) Tell us about when you first became interested in poetry. Who were your first poetic influences? When did you begin writing poetry? What do you think poetry does or can do for us today and does this differ from your earliest conceptions of what poetry is/does? etc.

I first became interested in poetry in high school—I really liked the Beat poets, particularly Gary Snyder. Allen Ginsberg I was half-scared of, but him too. I started writing—both poetry and fiction—during my sophomore year of high school, but not seriously; just as a lark. The first creative writing course I took was as a junior in high school from Tom Meschery, former center for the San Francisco (now Golden State) Warriors—Wilt Chamberlain once scored a 100 points on him (there were other defenders as well but Meschery was the primary one). He was a good teacher of creative writing generally and fostered my interest in poetry particularly—I remember on the first day we had to write a variation on W.C. Williams’ famous poem “so much depends/ upon/ a red wheel/ barrow/ glazed with rain/ water/ beside the white/ chickens” and mine was “so much/ depends upon/ the first sound/ of laughter/ shared/ between/ new friends.” Along with one or two other examples, he chose to read mine out loud to the class, which probably stoked my poetry writing ego a bit. As for what I believe poetry can do today vs. when I first started writing, I’d again refer to W.C. Williams, this time with regards to a statement he made to fellow poet Louis Zukofsky near the end of his life: “To write badly is an offence to the state since the government can never be more than the government of words.” That sounds melodramatic, and it is, but I do think it’s true. More so than just about anything else in this world, language matters, and poems are written out of particles and schisms of language. Sticks and stones may break my bones but words can never hurt me is bullshit—a smack to the face might hurt more in the moment, but the words leading up to it will in all likelihood last in your head longer. Your face will probably heal.

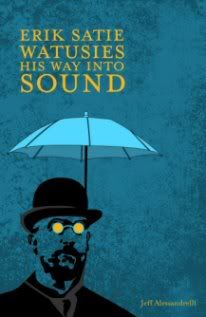

2) Give us some background on the creation, development, and gestation of Erik Satie Watusies... How does this collection differ from your previous collections or current projects? etc.

Erik Satie Watusies His Way Into Sound was originally conceived in a poetry workshop class like the one y’all are in right now. The final obligation for the course was to put together a chapbook of poems, one that had some type of overriding thematic concern. Going into the project I didn’t really have a subject; I had a bunch of disparate poems all written over the course of 8 or 9 weeks, all with different subject matters/ line lengths/ syntactical notions, etc. But I needed to come up with something. Actually, that’s a lie—due to the fact that since my first year in grad school I’ve consistently read a lot of serial/ longer poems (John Berryman’s The Dream Songs and Homage To Mistress Bradstreet, Wallace Stevens’ “The Auroras of Autumn,” Anne Carson’s Short Talks, a hefty amount of Jack Spicer’s work, Mathias Svalina’s serial-poem-chapbook Creation Myth, and a few months before the workshop I started working on Erik Satie Watusies His Way Into Sound) I wanted to come up with something—not for the class as much as myself really. Throughout the workshop I’d been listening to a lot of instrumental/ vaguely electronic music, particularly the group Boards of Canada (check them out, especially their albums Music Has the Right To Children and The Campfire Headphase), as well as the solo artist Brian Eno. Somehow this got me thinking about Erik Satie—before I moved to Lincoln I lived in Portland, Oregon, and the first year I lived there I’d discovered Satie’s “Gymnopédies” and “Gnossienne” pieces and listened to a mix cd of them and a few other Satie compositions every morning for about 8 months straight. I really liked that Satie cd because I didn’t really have to listen it; for me it was (and is) background noise in the best way possible. Soothing. While in Portland one night my friend Dylan had told me about how weird a dude Satie was, specifically that he tried to push his girlfriend out a window and only ate foods colored white. To make a long story short I listened to that same Satie cd for a couple of days while thinking about a longer project type deal, still liked what I heard/was inspired, checked out some books on Satie/by Satie and started working on the book. It came together as a final collection about a year or so later.

3) What is your favorite or most memorable poem from the collection we're reading? What about the poem, its process, or its inspiration makes it particularly remarkable for you?

My favorite poem is the “Erik Satie Watusies His Way Into Sound” prose poem on page 16. I like history—I minored in it as an undergrad—and I think the part about Napoleon/Caesar/Alexander the Great/Hercules is interesting. I can’t remember where I read it, but I’m 95% sure it’s true. I’ve also been to a lot of all-age punk shows and have seen my fair share of wilting mohawks.

4) What was the most difficult poem for you to write? Why? How did you overcome or think through these challenges?

They weren’t difficult to actually write, but all of the “sheet music” poems were difficult to transfer/ transpose onto the individual pieces of sheet music, especially due to the fact that I am horrible with computers. In the end they came together, and I think that for the most part they look good in the book, but they were by far the most difficult part of rounding together the manuscript. Your teacher helped me out a lot with them, and I am eternally grateful to him for that help.

5) What, to your mind, is the overriding concern of Erik Saite Watusies...? How do specific craft or poetic elements contribute to, intensify, or complicate to this concern?

This is probably a cop-out, but I’m not sure there is a specific overriding concern. Contextually I’d say it’s important to have heard maybe one or two Satie pieces of music before starting the book, but I’ve talked to a couple people who read the entire collection without listening to any of Satie’s music and according to them it didn’t make a whole lot of difference—they treated him as more of a character rather than a historical figure. Which is fine, I suppose, although I think listening to at least a couple pieces of Satie’s music—specifically the “Gymnopédies” and “Gnossienne” compositions perhaps—might make reading the book more rewarding. Very early on in the publishing process there was talk about including a Satie cd with the book, but that idea got shelved quickly because of conflicting rights to the music/ feasibility issues/ etc. I don’t know—we live in a rapid-fire, 24-7 world, and I realize that writing a book of poetry loosely based around the life/work of a French avant-garde composer that’s been dead for over 70 years might seem kind of silly to a lot of people. But I think Satie’s music stands up, and he was in the epicenter of what has since became known as “Modernism,” at least in terms of Western Culture—he worked on plays with Picasso and Jean Cocteau, hung out at Gertrude Stein’s place on occasion, and along with Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel is known as being one of the first “Modern” composers because of some of his harmonic/tonal innovations. He was an interesting guy. I suppose, then, the overriding concern of the book for me is making both Satie’s music and personality interesting on some level to the reader, and I hope I achieved that to a certain degree at least.

No comments:

Post a Comment